Talbot Park

Aaron’s research/case study on Talbot Park, a community renewal project initiated by Housing New Zealand in Glen Innes, Auckland.

Published on MfE Website, May 2008

Community Renewal – Housing New Zealand Corporation, Talbot Park, Auckland

Fast facts

Location: Glen Innes, Auckland

Site: 5 hectare block in Glen Innes, Auckland (including 1 hectare existing public reserve)

Completed: March 2007 and public parks completed May 2008

Client: Housing New Zealand Corporation

Partnership between: Housing New Zealand Corporation, Auckland City Council and the Glenn Innes Community

Design project teams:

Masterplan: Geoffrey Walker Urban Design and Planning, with HNZC and Auckland City Council

Detailed masterplan: Boffa Miskell with HNZC and Auckland City Council

Housing development: Architectus, Bailey Architects, Boffa Miskell, Common Ground, Design Group Crosson Clarke Carnachan Architects, Design Group Stapleton Architects, Design Group ASC Architects, Pepper Dixon Architects

Case study researcher: Aaron Sills, Sills van Bohemen Architecture Ltd

Key Statistics

Existing dwellings: 167 Housing New Zealand Corporation residential units

Existing residential density: 33.4 units per hectare

Redeveloped dwellings: 111 new and 108 refurbished residential units

Redeveloped residential density: 43.8 units per hectare

Budget: $46 million

Residential Density 8b Zone: Adjacent to residential areas one unit per 100m² and up to four storeys (maximum 17m)

Introduction

The Talbot Park development is part of one of six community renewal projects initiated by Housing New Zealand Corporation (HNZC) in 2001.5 The primary goal of these community renewal projects is to “address social exclusion and foster strong sustainable communities”. The projects are in areas of existing HNZC housing in Christchurch, Wellington, Rotorua, Manukau City, North Shore City and Auckland City.

HNZC is by far the biggest provider in the social housing market in New Zealand – it expects to build 1,000 houses a year. In comparison, other social housing providers such as the New Zealand Housing Foundation build 80 new houses, and Habitat for Humanity build around 20 new houses per year.

Talbot Park sits in the suburb of Glen Innes, in the Tamaki area of eastern Auckland. Around 16,000 people live in the area in about 5,000 dwellings, and HNZC is the owner of 56 percent (or 2,840) of those dwellings. Talbot Park consists of a 5 hectare block of land bounded by Pilkington Road, Point England Road and Apirana Avenue. It was chosen as a HNZC community renewal project to demonstrate quality urban design principles, sustainable building practices, community partnerships and innovative architectural design in medium density housing.

Talbot Park within the wider Tamaki context.

Talbot Park neighbourhood context.

A wide range of ethnicities are represented in Glen Innes, with about half the population being of Pacific Island descent. It is a low socio-economic area with a high dependency on social assistance. Talbot Park’s ethnic mix is approximately 50 percent Pacific peoples, 20 percent MÄori, 20 percent Asian and 10 percent Others (including Iraqi, Iranian, Fijian Indian and European). English is the second language for most residents.

Prior to the Talbot Park Renewal Project (the Project), 90 percent of the existing HNZC housing stock in the Tamaki area consisted of two or three bedroom dwellings, with more than half being built prior to 1960. The majority of HNZC applicants required further variety in the number of bedrooms. However, applicants needing four, five or six bedroom houses would normally have to wait more than twice as long for a house to become available as people wanting two to three bedroom units. For example, in 2004, the average time on waiting lists for a three bedroom house in Tamaki was two months, while for a five bedroom house it was nearly five.

The concentration of HNZC properties in the area has attracted other privately owned low-income rental housing, further concentrating deprivation in the Glen Innes area. Much of the private rental housing is of a lower grade and is being maintained to a lesser extent than the existing HNZC stock. High concentrations of functionally obsolete housing in one locality have compounded problems of social exclusion.

The existing Talbot Park site consisted of 1960s public housing in poor condition. The site had a history of ongoing security and social problems, partly associated with the internal public park based on the ‘Radburn’ concept. The public park ran through the site, with HNZC properties backing onto it. The urban designers (Geoffrey Walker from Urban Design and Planning, with HNZC and Auckland City Council) found the current relationship between the HNZC properties and the park lacked boundary definition. This resulted in residents feeling unsafe in the Talbot Park public green spaces. Increasing the sense of safety in the area became a primary objective of the Project.

The Project was launched in 2002. It was seen by HNZC as a partnership with the local community and Auckland City Council. It involved major refurbishment of 108 existing dwellings (apartment units within nine apartment blocks) and the construction of 111 new dwellings to achieve a total of 219 dwellings with a variety of typologies. The public spaces and street network of the block were also radically changed.

Project objectives

The philosophy behind the HNZC community development approach was aimed at increasing participation by involving local people and resources in addressing local problems to improve the wellbeing of the individuals who live there and increase the amount of social capacity available within the community. The primary objectives of the HNZC community renewal programme were to work with the community and a range of other agencies to:

- improve and enhance the physical environment and amenities

- provide targeted needs-based tenancy and property management services

- use principles of community development and implement community-led solutions

- create links to programmes that increased resident employment and business growth

- provide access to affordable and appropriate community services and facilities that responded to changing community needs

- improve neighbourhood safety and reduce crime

- build social networks to facilitate residents supporting each other.

Project process

A project office was set up in the centre of Talbot Park as the first part of the Project. This office, located in two existing neighbouring HNZC houses, served as both a base for project co-ordination as well as a location for the provision of all HNZC services in the area. This was intended to demonstrate the organisation’s commitment to the project and to combat the likely local perception that change was being driven from the outside. HNZC now intends to use this local presence approach for all future community renewal projects.

Masterplan

Geoffrey Walker from Urban Design and Planning developed an initial masterplan in association with John Tocker and Morgan Reeve of HNZC, as well as Auckland City Council representatives who participated in joint workshops. The masterplan was initially called a ‘structure plan’ and then later a ‘neighbourhood plan’ because the term ‘masterplan’ was seen as giving the impression that HNZC was not working with the community.

The initial masterplan included a site layout of public and private space, streets and housing typologies, and set several guiding design principles for the development, including:

- removal of the existing spine of public park through a land swap with Auckland City Council to create two new parks with improved urban relationships to residences (it retained the same total area of public park)

- provision of a new internal road layout, increasing site permeability and connectivity, with narrow streets to slow traffic

- creation of improved street and park frontages with further dwellings overlooking public areas

- provision of a range of medium density building typologies catering for a variety of family types – resulting in units ranging from one bedroom apartments, to eight bedroom family houses

- placement of higher density apartment buildings against the busiest road (Apirana Avenue)

- location of children’s facilities on public open space in the quieter interior of the development

- limiting total units to 205 (in order to be at an acceptable building height and density for the community, and for HNZC long-term social housing management).

Talbot Park masterplan.

Change to Residential 8 zoning

During the period from 2000 to 2002, there was public debate in Panmure and Glen Innes over the issue of increasing urban density. Auckland City Council notified the new Residential 8 zoning,6 which was aimed at allowing higher densities in the areas determined as ‘growth corridors’7 in Auckland. Talbot Park was earmarked as the first area to have its zoning changed to Residential 8. Because of public opposition to high densities, it was decided to reduce the density in Talbot Park. The 4 hectares of building lots would have a theoretical capacity of 400 units and a height of four storeys under the Residential 8b rules. In reality, this would have required underground car parking spaces. The Apirana Avenue edge of Talbot Park is the only area where HNZC might have extended to four storeys, because extra building height would have been more in scale with the wide road and created a buffer for the rest of the site from the busy road.

Talbot Park detailed unit masterplan.

Once the initial masterplan was approved by the Minister of Housing and Auckland City Council, Boffa Miskell was engaged to develop a detailed masterplan (called a neighbourhood plan). Boffa Miskell led a collaborative process with the community (not only HNZC tenants), Auckland City Council and HNZC staff. This consisted of a series of community workshops, focus groups, surveys, open days and newsletters. Boffa Miskell envisaged this as a ‘bottom-up’ approach, rather than ‘top-down’. There was initial scepticism about the amount of community collaboration to be undertaken, but Doug Leighton of Boffa Miskell noted that this was soon dispelled once the process was under way, and the benefits of the community collaboration became evident.

The detailed masterplan developed through this process retained the configuration of the initial masterplan and general disposition of buildings. Building typologies were developed and presented to the public, and the apartment block closest to the northern reserve (Atrium Block) was reconfigured in order to achieve more surveillance of the open space. Higher density apartments were positioned along the busy street of Apirana Avenue. Concepts for internal roads were further refined to include rain gardens (partly subsidised by Infrastructure Auckland and subsequently Auckland Regional Council grants).

The initial masterplan was presented to the Auckland City Urban Design Panel and several panel recommendations were made. These were addressed during the development of the detailed masterplan (neighbourhood plan) and the revised scheme was re-presented to the Urban Design Panel.

Developing this Neighbourhood Plan before bringing architects on board to design buildings was an essential element of the process. This approach allows the site layout, public spaces, interconnections, public safety issues (in relation to site layout), to be worked through an urban design process before the architects become involved and the focus switches to the buildings and their immediate surrounds. (Stuart Bracey, HNZC project manager.)

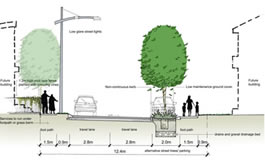

The roading network and parking in the detailed masterplan became an issue because of a conflict between urban design-based road width requirements and those required when new roads are vested in council under the “code of urban subdivision and development”. There was also opposition to the incorporation of rain gardens in roads being vested, because they would complicate council maintenance. These issues were worked through with Auckland City Council, through a joint project team process. For transport engineers and the New Zealand Fire Service, wider roads were necessary to allow passage for emergency vehicles, while for the designers, narrower roads (10m wide) were necessary to reduce vehicle speeds and to increase safety and the sense of community and place. In the end, reduced road widths were used, with a road reserve width of 12.4m, including a carriageway width of 5.6m and 2.0m of parallel parking on one side of the road.

Stuart Bracey, HNZC, notes that the internal roads were designed to be 30km per hour but, at the time, there was no way of designating this speed on a public road. Auckland City Council now has a bylaw that allows lower speed limits, and HNZC is hoping to have speeds in Talbot Park reduced legally.

Talbot Park road section.

The new apartment developments have a parking ratio of one car park per unit and no visitor parking spaces, which was lower than the Residential 8 requirements of one car park per unit and one visitor park for every five resident parks. However, existing data on HNZC tenants’ parking requirements, as well as the creation of new roads with parallel parking, was used to justify this reduction to Auckland City Council.

The front yards of the detached family houses incorporate parking for cars and small areas of planting to separate children from vehicle manoeuvring on and off the road. There is also a 10m x 10m fenced and secured rear yard for each detached house, to allow children to play safely.

Building development

Doug Leighton of Boffa Miskell had the role of project leader during the development of the detailed masterplan, and once that was complete he briefed and co-ordinated the architects who were to work on individual buildings. Boffa Miskell was also the statutory planning consultant and landscape architect for the entire project, with responsibility for co-ordinating each of the architectural firms working on the project on the landscaping for individual lots.

HNZC was anxious at the beginning of the project to avoid too much uniformity in the building designs. Both the variety of typologies utilised and architects employed have resulted in architectural diversity across the project. Individual multi-unit block designs vary, but none have been designed to avoid repetition within the block (apart from superficial colouring in the Triplex apartments).

Two storey duplexes.

Three bedroom terraced housing.

Two bedroom apartments.

The existing three storey Star Block apartments (nine blocks, with 108 units in total) were retained and renovated first. This served to demonstrate goodwill to the local community by dramatically improving the environment for tenants. Open homes were conducted to display the renovations to the community. Improvements included adding decks, punching through and glazing ground floor lobbies to open them up and make them safer, new roofs, stainless steel kitchen benches, heating and landscaping. Externally, the alterations were not particularly in keeping with the original architecture but they provided practical improvements for tenants.

Existing Star Block apartments prior to refurbishment.

Refurbished Star Block apartments.

The 167 existing HNZC tenants were relocated at different times during the renovations and were all given the option to return. However, the Project provided the opportunity to implement medium density residential living rules for tenants that were stricter than in previous tenancy agreements. These included such things as: no dogs allowed (found to be a big safety and noise issue for the community during consultation), no pets in apartments, no unreasonable parties after 10pm and tenant responsibility for their own visitors and their visitors’ parking behaviour. Tenants sign on to these living rules and are moved if they cannot comply. All of the people who have been given the opportunity to live in Talbot Park have accepted these conditions on moving in. A tenancy manager (based onsite in the Project office) deals with the enforcement of the rules as part of their job. A ban on smoking within dwellings was also considered but not pursued.

Evaluation of urban design principles

Context

A key feature of the Project was the restructuring of public space, including parks and streets. A land swap with Auckland City Council has meant that the long and narrow Talbot Park, which caused many safety issues with its position at the rear of dwellings, has been transformed into two individual parks that are well overlooked by housing. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles have been followed, with careful design for maximum surveillance, use of permeable fences between public and private open space and vandal-proof fixtures and fittings.

The higher density apartment blocks were positioned along the busy street of Apirana Avenue in order to shield the internal areas of the site, while detached houses were located closer to the eastern side of the site where they related better to the surrounding detached houses. The higher density buildings also have a direct connection to the train station to the north of the site.

Character

The general aesthetic quality of architecture in the development is high. There is, however, a sense of impermanence in units where fibre-cement sheet cladding has been used, and the Triplex apartments are painted in bright colours in a way that may characterise them as ‘social’ housing. A sense of identity for the community comes from the diversity and quality of the buildings. This should develop further once the landscaping of the parks is completed by Auckland City Council and they become a focus for the neighbourhood.

Stuart Bracey of HNZC notes that the brief for the detached houses was to have a ‘Pacifica’ aesthetic. The mix of colours and the horizontal timber battens over the steel cladding lends a Pacific character to the designs.

Choice

Both the variety of typologies utilised and the architects employed have resulted in architectural diversity across the project, giving further choices in housing to tenants. Out of a total of 219 units, there are 20 that are fully accessible to wheelchair tenants, 16 that are accessible friendly (served by lifts), and 15 family homes have accessible ground floor bedrooms and bathrooms. Accessibility was a focus for designers. However, cost was a major factor in decisions on the degree of accessibility in units (for example, the electronics for a self-opening door can cost $4,000).

With the detached family houses, there are two general plan arrangements with kitchens either at the road end or in the middle of the house, and between four and eight bedrooms. This provides for the high demand large family homes required by HNZC tenants. These homes were also designed to accommodate a variety of cultural lifestyles. Having a second living area off the entry that can be used for formal reception of guests has proved to be a flexible arrangement for many different cultural groups. Single attached garages are also being used in a flexible way by tenants – as an additional room for a gym or entertaining, for example.

The number and type of units are as follows:

- 108 units refurbished in nine Star Blocks (three storey apartment buildings); architects: Pepper Dixon; construction: Canam Construction

- four, three bedroom Duplexes; architects: Bailey Architects; construction: Fairway Homes; 32-38 Salima Talagi Street

- 24, two bedroom Atrium units; architects: Architectus; construction: Pepper Dixon and Federal Residential (design-build novated); 340 Apirana Avenue

- 21 large family homes (four to eight bedrooms); architects: Common Ground; construction: NZ Built

- 24, two bedroom apartments; architects: Design Group: CCCA Ken Crosson; construction: Canam Construction (design-build novated); 360-366 Apirana Avenue

- 16, three bedroom terrace houses; architects: Design Group – Neil Cotton and Craig Roberts; construction: Fairway Homes (design-build novated); 1-33 Tippett Street

- four, one bedroom accessible units; architects: Pepper Dixon; construction: GJ Gardner; 51-57 Tippett Street

- 18, two bedroom Triplex units; architects: Pepper Dixon; construction: Canam Construction (design-build novated); 45-49 Tippett Street.

Connections

Connections through the site were considered from the first discussions. Designers focused on the existing flawed street, park and building layout of the site, with the defective internal public park causing major problems.

New streets were created, and the project team debated the form of these internal roads and the character they should have. They set the goal to slow traffic and to make streets that could be used safely by the community.

Creativity

A diverse group of people have brought their creative talents to this project. This includes professional designers and architects, members of HNZC, Auckland City Council and community members.

The employment of a variety of architectural firms has increased the diversity of buildings in the development – which HNZC was anxious to achieve. HNZC brought all the architects together during the design period to ensure their designs related well to each other. These meetings provided an opportunity to discuss colour themes and the general landscaping with Boffa Miskell (because all soft landscaping was separate from the building construction contracts).

Custodianship

The Project combines the provision of high-quality medium density housing with the creation of community networks and community spirit. HNZC was clear from the beginning that the Project was not just asset development and refurbishment, but the improvement of the whole community.

Sustainability and low-impact design were major factors in the Project, both in the design of dwellings and the street and exterior space design. Sustainability issues were addressed through the incorporation of:

- higher levels of insulation than code requirements

- passive venting in aluminium windows

- range-hoods in all kitchens to extract damp air and reduce internal condensation

- solar water heating in some units – including all the Atrium apartments (capital cost approximately $6,000 per house and $2,000 per apartment)

- rainwater collection into garden tanks supplying toilets and garden irrigation in some of the detached houses (capital cost $4,000/house) and one apartment complex

- rain gardens within the streets for treatment and detention of stormwater

- permeable paving to reduce the amount of stormwater leaving the site

- a detention tank system to clean out solids from the stormwater of the large parking areas beside the Atrium apartments (capital cost $50,000 – viable only through an Infrastructure Auckland grant).

Collaboration

HNZC’s philosophy was aimed at increasing community participation in the project and developing community capacity. HNZC set up a project office in the centre of the project to demonstrate its commitment to collaboration directly with the community.

Collaboration between organisations was also a strong feature of this project, with a bottom-up rather than top-down approach to design. A series of community workshops, focus groups, surveys, open days and newsletters was used to develop the Project.

There seems to have been little collaboration with the owners of the few private properties (both rented and owner occupied) in Talbot Park to encourage upgrading of their properties. This may, however, occur naturally over time.

Value gained

Economic

The recent HNZC developments generally have a higher building and urban design standard than private low-cost rental developments in the area. This standard of public housing decreases tenant turnover and better meets the needs of HNZC tenants. HNZC also owns a large percentage of housing stock in the Tamaki area, so any increase in quality positively affects the overall value of other HNZC housing in the area.

HNZC also feels that the demand for larger dwellings from those on low incomes is being ignored by the private sector. The use of design-build contracts with construction companies was seen as a way of encouraging the private sector to begin to consider, and eventually provide for, low-quality housing.

Family houses.

Contractors on the project were required to employ local people where possible. This led to the employment of 25 people from the area, with five becoming permanent employees.

Social/cultural

The Project has resulted in a low tenant turnover in Talbot Park. At the beginning of the project, tenant turnover per annum was about 50 percent, it now sits at about 5 percent. This is likely to be because of the development of housing that is better suited to tenants’ needs, and the greater investment in onsite tenancy management. The value to tenants is reduced occupant stress, as well as social and economic benefits for those who do not have to move to alternative accommodation. The management of the mix of tenants is also an important part of the success of the project.

An outcomes evaluation of the six HNZC community renewal programmes was undertaken from 2005 to 2006. The evaluation found that the programmes were moving towards achieving all their targeted outcomes and were demonstrating examples of ‘best practice’. Highlights from the key findings were that:

- the projects engaged with their local communities

- individuals were empowered

- there was increased resident pride and ownership

- reduced social exclusion fostered strong, sustainable communities

- the physical environment was improved

- outsider perceptions of community renewal areas improved

- there was an increase in available and responsive housing services.

A key success for the project was gaining public and community acceptance of the Talbot Park detailed masterplan by addressing the main crime and safety concerns raised by residents. A safe public environment has been created through the reconfiguration of the area, together with better streetscapes and lighting.

Sustainability

Several sustainability and low-impact urban design features were incorporated into the Project. The design of the houses has resulted in healthier living environments for the tenants, with warmer, drier and better ventilated houses. Solar water heating and rainwater collection units are being currently monitored to assess the likely cost reductions to tenants and HNZC.

Lessons learnt

Housing interventions alone cannot achieve HNZC’s community renewal vision. Reducing social exclusion requires partnership with others, such as Auckland City Council, to create a physical environment with good-quality housing in a healthy, safe and sustainable environment that is appropriate to the needs of the families and community.

The Residential 8 zoning change by Auckland City Council, with the threat of increased density, resulted in approximately 800 submissions mainly in opposition to the plan change. This meant the project team had to work hard to ensure there was good community consultation and participation in the project.

Doug Leighton of Boffa Miskell initially had in mind the concept of Home Zone, or Woonerf, as a goal for the internal streets of the development. In the end, narrow streets with rain gardens and parking on one side were chosen (Residential 8 dimensions). This has been successful in slowing traffic, but HNZC is also working to have the speed in these streets reduced to 30km per hour under a new Auckland City Council bylaw.

The interpretation of car parking rules by Auckland City Council caused difficulties.

We were eventually allowed to offset the new street parking against the visitor parking required. HNZC research had shown that family houses would have high parking demand whereas the apartments would have low demand, and are underutilised. (Doug Leighton, Boffa Miskell.)

Starting the project without comprehensive survey information also caused problems, according to Doug Leighton. A false assumption, based on a lack of survey information, resulted in a row of poplars requiring removal – and this became a sticking point, despite their exotic status. Related information on an overland flow path was also unavailable at the outset and subsequently affected the design of the area by requiring gaps between buildings, extra retaining walls and raised floor levels.

The process of building procurement has also caused issues. HNZC used a traditional lump-sum tender process for all detached family homes, duplex houses and single bedroom units, and a design-build, arrangement for all multi-unit buildings. In a design-build, arrangement the building company contracts to the client to provide a building for a fixed price based on the preliminary design, and the architects are novated (contracted directly) to the building company at the end of the preliminary design stage. The main contractor therefore has more influence in the detailed design and construction documents as they are developed – which can lead to better resolution of construction detail but also pressure to reduce costs, without the knowledge of the client.

Both procurement systems had their strengths and weaknesses. Design-build saved time but there was some loss of control; HNZC expected to take part in a design evolution process with the contractors but the contractors did not believe this to be the case. With a traditional process of lump-sum tendering, the client has control over the design and more flexibility; when designs evolve there is also increased transparency on costs.

Permeable paving was used in some parts of the project to reduce the amount of stormwater leaving the site. However, this has generally been disappointing because it is prohibitively expensive and relies on underground drainage.

To allow for at least a full year of occupation to test systems, a post-occupancy evaluation was initiated at the end of 2007. The Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority (EECA) has tested solar systems and Landcare Research has evaluated the water harvesting systems. Occupant satisfaction evaluation of both the Atrium apartments and the family homes is underway, with other housing typology evaluation surveys to follow.

Conclusion

In January 2007, the Talbot Park community renewal project was fully occupied – although work on the two new parks was completed by Auckland City Council in May 2008. The project is the first HNZC community renewal project completed in Auckland and to test the Auckland City District Plan’s Residential 8 zone.

The Project has fulfilled the original intentions of the participants to test several community collaboration, urban design, environmental and building typology initiatives. The Project has also been a successful exercise in collaboration between many organisations, including HNZC, Auckland City Council, Auckland Regional Council and Infrastructure Auckland, as well as several consultants and contractors.

5. A fundamental endorsement for the project is that HNZC housing applicants are now specifically requesting to live in the Talbot Park project area.

6. See http://www.hnzc.co.nz/hnzc/web/housing-improvements-&-development/property-improvement/community-renewal.htm for further

information

7. See Res 8 Strategy for further information.

H See www.aucklandcity.govt.nz-default.asp for further information.

Aaron Sills